In the Tibetan Buddhist context in which I practice, hope and fear are considered to be essentially two sides of the same coin. I don’t know the original Pali Canon teachings well enough to know if the teaching goes all the way back through Buddhist history. I assume so.

From the point of view of ego clinging, hope and fear are so closely related they might as well be the same thing.

To be clear, this is not about the kind of hope that might be connected with a larger view of compassion:

May all beings have happiness and the root of happiness

May all beings be free of suffering and its causes

etc

Compared to greater aspirations of compassion, normal hope is inextricably connected to apprehension. I want things to work out for me. I don’t want to lose what I have. The “I” in those sentences is doing a lot of work. There is a kind of an “I” that Tsoknyi Rinpoche calls the “Mere I,” but our normal “I” is more or less made out of hope and fear. The hope that I get what I want and get to keep everything together is essentially the same as the fear that I will lose it, not get what I want. Take a step back and they are the same, but get caught in them and they seem to have very different flavors. Being caught in hope or fear obliterates a greater awareness, a bigger view, whichever flavor manifests.

So now in this time of the COVID-19 pandemic, the balance has shifted from hope toward fear in general. Certainly it has for me. By now the fear is less acute — social distancing has helped a lot and in general we feel safer than we did at first, maybe, depending on where we live, our situation.

When I’m not caught in the fear of our current time — and make no mistake, sometimes I am — I find it’s oddly a bit helpful to have shifted a little bit from hope, at least in my photography.

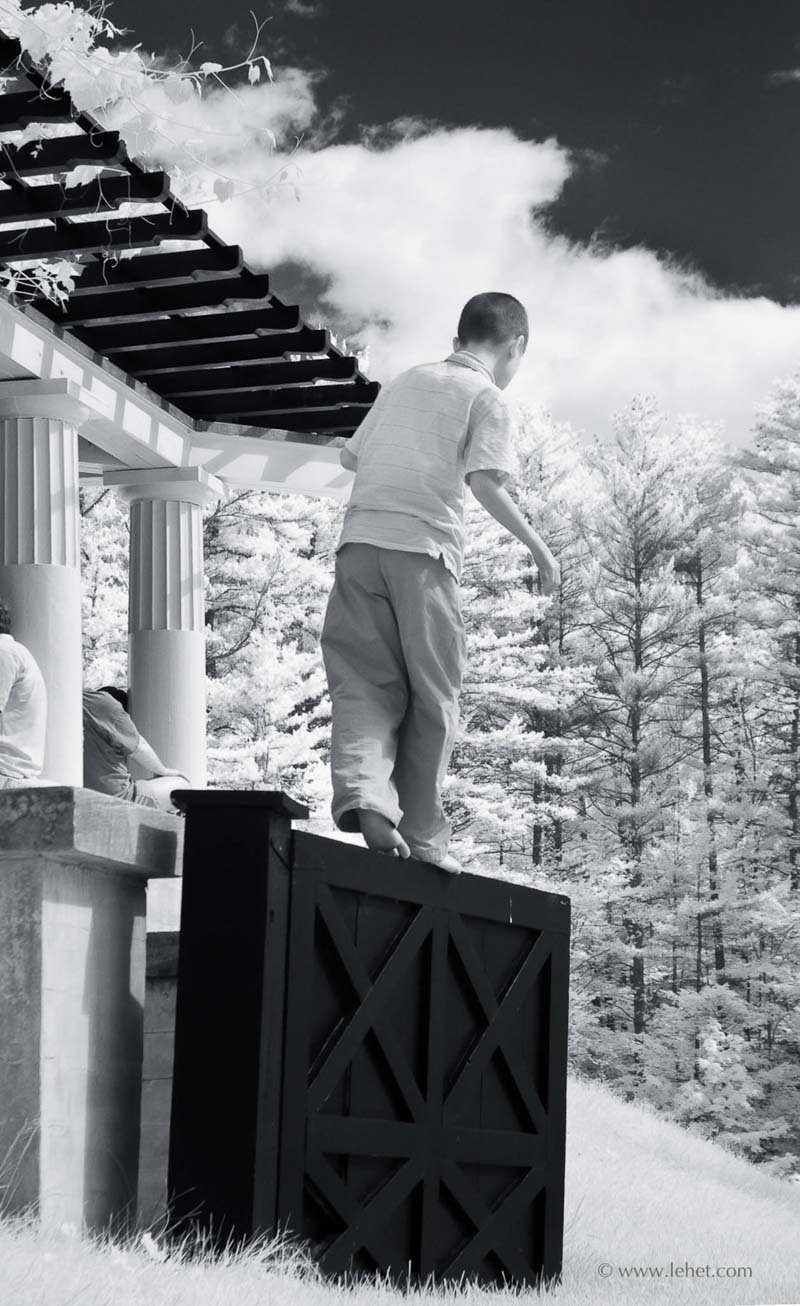

I may have mentioned that some of the most fruitful times in my development as a photographer have been in times when I had little hope that making exposures would yield anything, when working with a camera was more of a pure exploration, more like play. I think most of my worst pictures were from the time I was most serious, when I used a view camera and big film and worked in my own darkroom. Though I have well over a hundred pounds of silver-infused paper and film, I have few images made that way posted on my website now. By contrast I made great progress in the time when I had no darkroom and digital cameras were new and sucked so badly that there was no chance of making a great print or selling something from that work. It was freeing and fun. As digital cameras got better, and then really good, the continuum of hope-for-success has shifted with the quality. And make no mistake, with the better cameras and the better (and sometimes quite old) lenses I’m using now, better results are easier to come by. I just have to keep some sense of that freedom, stepping back from some kind of hope for fruition. Right now, with the world imploding, that hope is easier to let go of.

Hope does sometimes put wind in the sails, it keeps one going. In a pursuit like photography — a mix of the worldly and the realm of light and mind and awareness — hope sometimes makes the whole thing possible on a long term basis. But it also blocks the light of open possibility. Hope stands in front of the lens like a big oaf. Hope gets behind you like a big oaf and gives you a shove forward. It’s up to us to keep our balance after that shove, to move so it’s not blocking our vision.

Now, in this dark time, all the galleries are closed. Who knows when they will be open, when people will feel brave enough to go in them and have money to spend on prints? And still I work on photography, more free from the burden of hope. Sometimes I spend time — lots and lots of hours these days pass uncounted — hiding from the fear in the realm of glowing pixels, looking through my lightroom catalog, seeing what potential I can tease out of images already exposed.

I care less about the current state of art photography. I am enjoying making beautiful photos these days, though I make other kinds. But what I need, and what I’m happy to bring into the world, is something very beautiful. It’s a different emphasis for sure.

I think of “How to Cook Your Life,” the Zen book by Uchiyama and Dogen.

In this book, after some discussion of how food might be prepared by the cook in the monastery, Uchiyama describes the existential situation. We don’t know what will happen in the night, and yet the cook prepares for the meal the next day.

“In preparing the meal for the following day as tonight’s work, there is no goal for tomorrow being established. Yet our direction for right now is clear: prepare tomorrow’s gruel. Here is where our awakening to the impermanence of all things becomes manifest, while at the same time our activity manifests our recognition of the law of cause and effect.”

Right now we really don’t know what tomorrow will bring. We keep working if we can.